Odd thing happened on my way out of the LCS

last week: I left without buying a #1 issue. A few weeks ago in an attempt to

best comic book super fan Aaron Myers (whom you should most definitely follow

on twitter: @AaronMeyers) I

emailed the men of Panel

Culture this question: 'What makes a

good first issue?' (ep. 55). As soon as I hit 'SEND' I realized that I have

a blog and access to one of the greatest comic book blogger minds this side of

Kuala Lumpur, Justin

Giampaoli. So I asked Justin to weigh in on this #1 topic. Here's what we

said:

Odd thing happened on my way out of the LCS

last week: I left without buying a #1 issue. A few weeks ago in an attempt to

best comic book super fan Aaron Myers (whom you should most definitely follow

on twitter: @AaronMeyers) I

emailed the men of Panel

Culture this question: 'What makes a

good first issue?' (ep. 55). As soon as I hit 'SEND' I realized that I have

a blog and access to one of the greatest comic book blogger minds this side of

Kuala Lumpur, Justin

Giampaoli. So I asked Justin to weigh in on this #1 topic. Here's what we

said:

Keith: In the last ten months I

have purchased thirty-six #1 issues. That number is slightly skewed by DC's New

52. Simple math says that that turns out to be about three #1 issues per month.

That's a lot of starts and a lot of do-overs. Now, some of those thirty-six

were limited series that have ended (The

Strange Talent of Luther Strode) or will end soon (Planetoid, Spaceman). For

every series that ends, there are ten more to take its place. First issues, it

turns out, are like those creaky black-and-white zombies, tireless, relentless.

But are they disposable? All this going #1 (sorry can't resist) makes me a

poorer man. Am I, however, wiser as well? First, let me set some guidelines and

a parameter or six before diving into some examples.

A first issue is so suffuse with anticipation

that it is (almost?) genetically predisposed to disappoint. At its best, it's

an exercise in frustration, even if that frustration comes from having to wait

a month for the next issue, a first-world problem to be sure. In theory, a good

#1 should be no different than a good #33 or #367, but that's not the way it

works. A good story may be a good story and therefore transcend its order in a

series. A first issue … that's different (special?) isn't it, if only because

it is 'the first?'One of my least liked comic book criticism crutches is the phrase 'decompressed storytelling,' which sounds to me like shorthand for 'I'm bored, but can't (won't?) quit and move on, a reverse 'it's not you it's me' kind of argument. For me, every story is a Gandalf, it is never late, nor is it early, it arrives precisely when its author means it to and that goes for beginnings, middles and ends (barring, of course, unforeseen circumstances like cancellation). The reader is a silent partner. If the author chooses to take the long cut or write a series of one-offs or decides to create a narrative that only makes sense when understood as a whole that's that. It's like that old joke: How many comic book readers does it take to change a light bulb? One to change it and ten thousand to say how much better the old light bulb was (one the internet, of course). Readers can't change how a writer writes, but they sure as hell can carp about it.

Again, a good story is a good story and in the case of a first issue it really needs to hook the reader. Duh. For me, a first issue (above all) must possess promise in either plot or character. As for setting, sorry, it's a handmaiden by its own design. I'm genre-diverse, but I need more than atmosphere, more than spaceships and lush English country-sides. If the spaceship (or glen) is sentient, we can talk. Promise also comes in the form of a theme or an idea as well. A story about 'loss' or 'identity' intrigues because those notions are recognizable and often reflect a character's arc i.e. the plot. Modern (and post-modern) literature limits plot and chooses to focus on abstract ideas, in other words a lot of navel-gazing -- Who am I? Why am I here? What does it all mean? -- you know, bullshit like that.

Before turning it over to the esteemed gentleman from San Diego, I want to recognize the importance of uniqueness. The more singular the story, the more it seems to possess a mélange of secret and intangible ingredients: cool-looking spaceship, O.K., living spaceship, better, conscious spaceship that flirts with the crew and is haunted by the soul of a belly dancer, even better. So, that's what I look for in the first issue: promise and abstraction.

Justin: Thanks, Keith. The gentleman from Vermont stands relieved. Well, you know I'm a statistics nerd, so I thought I'd initially respond with my own #1 count. I tracked the metrics for the last year and found that I sampled 91 new #1 issues in the last 12 months. Now, as you indicated some of these were finite mini-series that have since wrapped, and I also consume both mainstream titles and small press offerings. With those caveats aside, I only continued to support 17 of those 91 titles for any significant length of time. That's about 19%, which sounds abysmal to me. That means (approximately) that for every 5 books I try, I only like 1 of them enough to commit any form of ongoing financial support.

Before I dive into what I

think makes a "good" and compelling #1, I want to play devil's advocate

and take issue with the statement you made about "decompressed

storytelling," because who doesn't enjoy two bloggers getting up into each

other's faces? Come at me, Silva! I don't think citing decompression is

necessarily a lazy critical tool. If you take 6 pages to show two characters

walking across the street, something that could be done in 1 page, or even just

1 panel, and there's no story-driven reason why that length is relevant or

important to the crux of the narrative, then criticizing it for wanton decompression

just for the sake of itself can be a valid argument in my opinion[1].Off the top of my head, I was able to lump the factors that make a "good" new #1 for me into 5 categories. One, it has a lot to do with the strength of the writer and the artist. This might sound like a 'Master of the Obvious' comment to make, but let me explain. After reading comics for so many years and enduring the majority of lackluster creative output available -- 81% was that it? -- I've had to impose some fairly stringent guidelines to keep myself sane. I have to love the art, whether it's someone I'm familiar with or someone new to me. I have to love the writing, whether it's someone I'm familiar with or someone new to me. And, I have to love them both at the same time. I can't just love one or the other. Both have to be clicking or I just won't come back.

Two, there has to be a hook

for me. Some twist, some fresh take, coming at a genre or set of tropes with a

new angle, etc.; something unexpected or something that plays cat and mouse

with the audience and subverts reader expectations. Scalped #1 is an example of a strong hook I often use for people.

This book has been out for about five years and is just about to wrap up its

last two issues so I don't think this is a spoiler. Jason Aaron and R.M. Guera

offer a very compelling story of a violent drifter type named Dashiell Bad

Horse who is returning home to his childhood Native American home, the Prairie

Rose Indian Reservation. He's supposedly served in the military, done some jail

time, and bounced around the country. It's gritty and raw and in addition to

the art and writing working in unison to create this microcosm about a hidden

part of American society in utter decay, it did something else. In the space of

the first issue, he quickly gets embroiled with an old flame and the local

crime boss. He's knee deep in drugs, prostitution, gambling, gunrunning,

murder, and all sorts of racketeering. Well, on the very last page the twist

is... Dash is actually an undercover FBI Agent. I didn't see it coming and it

hooked me for a 5-year, 60-issue run.

Two, there has to be a hook

for me. Some twist, some fresh take, coming at a genre or set of tropes with a

new angle, etc.; something unexpected or something that plays cat and mouse

with the audience and subverts reader expectations. Scalped #1 is an example of a strong hook I often use for people.

This book has been out for about five years and is just about to wrap up its

last two issues so I don't think this is a spoiler. Jason Aaron and R.M. Guera

offer a very compelling story of a violent drifter type named Dashiell Bad

Horse who is returning home to his childhood Native American home, the Prairie

Rose Indian Reservation. He's supposedly served in the military, done some jail

time, and bounced around the country. It's gritty and raw and in addition to

the art and writing working in unison to create this microcosm about a hidden

part of American society in utter decay, it did something else. In the space of

the first issue, he quickly gets embroiled with an old flame and the local

crime boss. He's knee deep in drugs, prostitution, gambling, gunrunning,

murder, and all sorts of racketeering. Well, on the very last page the twist

is... Dash is actually an undercover FBI Agent. I didn't see it coming and it

hooked me for a 5-year, 60-issue run. Four, I think accessibility is very important for a new #1 issue. For me, I look for a precarious balancing act between telling me enough to engage me and make me care about the world or the characters or the ideas and being emotionally invested in the work, without treating me like I'm a 5 year old. I don't want to be told everything. I want to discover some of the mysteries for myself. I mean, I'll take the hot chick in my hotel room wearing just a pair of my boxers and sultry eyes over the fully naked woman screaming for sex any day, right? I don't want to be assaulted with expositional dialogue dumps and narrative captions that are telling me how I should be feeling at any given moment. I also don't want something to be so obtuse and laden with inter-textual Easter Egg references (Grant Morrison, Alan Moore, I'm looking at you guys) or some non-linear stream of consciousness style of scripting that I can't get a foothold on what's going on or why I should care. You read comics because you want to be entertained, right? Ideally that entertainment transcends to become art. But, bottom line, in a new #1 you have to do one thing: start a good story.

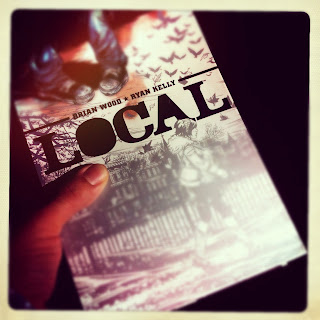

Lastly, I guess I'll throw a wildcard into the mix and talk about blind faith. There are one or two creators who have banked enough credibility with me on past projects that nothing I said above applies. Let me be clear that this is extremely rare and true of only two people I can think of at the moment: Paul Pope and Brian Wood. It doesn't matter what the book is about, the genre, the publisher, if it's a singular venture or they're working with collaborators, a one-shot, a mini-series, or an ongoing title. If their name is on it, I buy it without question, as a creative leap of faith. Usually their projects will meet some or all of the above criteria, but even if they don't, even if I'm not instantly hooked with that first issue, I keep buying it and see it through to the end because these guys have earned my loyalty and I trust them enough to ride with them to the very end. What new #1 issues have worked for you recently and why?

Keith: Leave it to you to find the one (or twenty) flaws in my argument. You're right, it's

not about how many first issues one buys, but how

many twos, threes and sixties(!). Because let's face it (in the most cynical

sense) what makes a good first issue is that you want to buy the next issue and

the next, etc. etc. So, logically, that's really all a #1 needs to accomplish:

get 'em to buy issue #2, which are usually a huge let down, but that's a

question for another day.

You had me laughing out loud

trying to parse my Gandalf metaphor. I wish I had done a better job explaining

myself, but then again I would not have gotten you to reveal your 'true colors'

about LOTR, so, ha! As an aside, I always thought a good subtitle for LOTR would

be: a long walk or stroll or meander through Middle-Earth. ANYWAY. What I meant

to say about decompressed storytelling is that it is the writer's and artist's prerogative

when it comes to how they want their story told. The first example that comes

to my head is Scott Snyder's current run on Swamp

Thing. He had an idea in mind about how he wanted to tell this story and

damned if he wasn't going to tell it his way no matter how long it took to

bring (re)create Swamp Thing. I had my struggles with that book, but the first

issue was 'good enough' that I spent the next seven or eight issues following

that story. So, I guess that made Swamp Thing

#1 a 'good issue' even though the storytelling was slow.

You had me laughing out loud

trying to parse my Gandalf metaphor. I wish I had done a better job explaining

myself, but then again I would not have gotten you to reveal your 'true colors'

about LOTR, so, ha! As an aside, I always thought a good subtitle for LOTR would

be: a long walk or stroll or meander through Middle-Earth. ANYWAY. What I meant

to say about decompressed storytelling is that it is the writer's and artist's prerogative

when it comes to how they want their story told. The first example that comes

to my head is Scott Snyder's current run on Swamp

Thing. He had an idea in mind about how he wanted to tell this story and

damned if he wasn't going to tell it his way no matter how long it took to

bring (re)create Swamp Thing. I had my struggles with that book, but the first

issue was 'good enough' that I spent the next seven or eight issues following

that story. So, I guess that made Swamp Thing

#1 a 'good issue' even though the storytelling was slow. Let's take another #1 that was

a story essential about a character walking from point A to point B. Prophet #21 (for all intents and purposes

a first issue). Again, using the GM (Giampaoli Matrix) it has everything. Why Prophet #21 was such a success is that

it did not depend on dialogue or intrusive narration. There is very little dialogue at

all in that first issue, but the narration never feels overdone or the dreaded

exposition dump. Prophet does little

more than walk and eat funny looking animals and yet I was totally invested. I

wanted to see more of John Prophet walking, using crazy tools, weapons and gadgets

and eating weird looking aliens. I wanted to know more about this character and

more about his world. Prophet #21

shows and tells in the best possible way by allowing the medium (art and words)

to work in concert to construct a narrative that could only be a comic book.

Let's take another #1 that was

a story essential about a character walking from point A to point B. Prophet #21 (for all intents and purposes

a first issue). Again, using the GM (Giampaoli Matrix) it has everything. Why Prophet #21 was such a success is that

it did not depend on dialogue or intrusive narration. There is very little dialogue at

all in that first issue, but the narration never feels overdone or the dreaded

exposition dump. Prophet does little

more than walk and eat funny looking animals and yet I was totally invested. I

wanted to see more of John Prophet walking, using crazy tools, weapons and gadgets

and eating weird looking aliens. I wanted to know more about this character and

more about his world. Prophet #21

shows and tells in the best possible way by allowing the medium (art and words)

to work in concert to construct a narrative that could only be a comic book.I like your 'wildcard' and it's something I considered – the credibility of 'blind faith.' Back in the mid-80's there was nothing by Frank Miller or Bill Sienkiewicz that I would not have bought, same goes for Howard Chaykin. Those were 'my guys' and I am nothing if not brand loyal. That's not the case now. Those creators have changed and so have I. Based on The Strange Talent of Luther Strode, I will buy whatever Justin Jordan and Tradd Moore do next (together and individually) be it Strode or anything else because they've built up credibility with me. I'm in for at least 3 issues (again a topic for another day ... how long do you give a series before you bail?) on the next iteration of the Strode story. I did not include this is my prior missive because I considered it too obvious. While one is in the throes of one's particular mania Paul Pope, Brian Wood, Frank Miller, Becky Cloonan, etc., one is in for the long haul and not just the first issue. In that sense #33 is no more important than #1, because one is buying them for a different reason, merit is a given. I would make another metaphor here (I'm almost out of time) about having bought EVERY Led Zeppelin tape (even Presence and Coda) when I first discovered Zeppelin because my mania knew no bounds and I could not discern. It was Zeppelin. COME AT ME Giampaoli!

Justin: I think you summed up this decompression beef nicely. Have a point!

Writers using a slower, more thorough pace, what's become modern comic book

parlance for 'decompression,' is absolutely their prerogative - provided it

has a discernible point. It's interesting that you mention Hell Yeah because it was certainly a new #1 that seemed to fail for

both of us. However, for me, it wasn't really the decompression that killed it.

It just failed almost all of my other GM (heh) criteria. I thought the art was

fuzzy, sloppy, inconsistent and uninspiring, the story seemed like it was a

derivative blend of Kick-Ass and Sky High, and it was trying to do the superheroes-as-flawed-paradigm analysis (while being extremely expositional

in the process), but didn't seem to bring anything unique to that particular

table. Your mileage may vary.

I'm glad you brought up Prophet #21 too, though I can't resist

being "that guy" and saying it's disqualified because technically

it's not a new #1 ("HAW-HAW!" - Nelson) even though it functionally

is one, because it's a great example of a strong debut. You mention wanting to

know more about John Prophet's world, and that leads me to introduce another concept,

which is world-building. I think strong #1 issues should make an effort to

world-build. Now, maybe there's some overlap here with a couple of the

categories already established, a) being unique or fresh and/or b) having a

strong hook. I guess it depends, again, on how you really define hook. I get a

little bugged when people interpret hook

as meaning a twist, like a twist

ending. I guess hooks can be twists, but twists aren't the only type of hook?

Anyway, Prophet is a grand example of world-building that doesn't stop to get expositional, yet remains

accessible and intriguing enough to pull you right in and leave you wanting

more. All of his hobbiting around served this precious point, to organically

tour us through the world that Brandon Graham set out to build, with the aid of Simon Roy on that first issue.Maybe I'm diverging a little here, but I see a lot of other tangential questions popping up here which are maybe outside the scope of this discussion. You mentioned The Strange Talent of Luther Strode, but that was a mini-series. So, do you thing the factors change or skew slightly when writing a new #1 for a finite mini-series vs. an ongoing? You also mention the first 3-issue arc of Conan The Barbarian. Do you think the factors for writing a 'good' first issue change based on how long the arc will be? I'm generalizing, but most modern on-goings will have 5 or 6 issue arcs. Brian Wood specifically said that his writing changed by having to condense everything into 3-issue arcs. Maybe this means more densely told stories, more compressed vs. decompressed (ugh! that word again!) storytelling, more to offer, more value to hook someone in the first issue. Speaking of value, does price point factor in to your decision-making process about a "good" first issue? Vertigo has been pretty good about offering some of their new #1 issues at an introductory $1. Your precious Spaceman #1 was $1, no? Does a book being $2.99 vs. $3.50 or $3.99 influence you specific to your decision to continue?

Keith: Precious Spaceman? You wound, sir. You wound. I'd like to say that price

matters and maybe it does for the most risk averse when it comes to trying a new

series. But a buck is a buck, and who among us would not shout out ''I'd buy[2] that

for a dollar!'' if issue #2 or #172 bore a similar cover price. My discretionary

income for a particular week often dictates if I'm willing to take a chance on

a number one and even then I try to pre-order through my LCS and have the issue

on my pull-list. I can't say for sure if the length of a story-arc would sway

me to pick up a first issue -- oddly enough, it is a factor for me when buying minis, so go figure -- it really

depends the mood I'm in at the moment. This brings up another discussion for

another time: when do you drop a series? I feel like there is an unexploited

market out there for self-help for comic book fans when it's time to let go of

that long-time favorite when it's not working for you anymore. Other worlds,

gunslinger, other worlds. O.K. Last question: In the last twelve months, what

are your favorite two number one issues that you've read?

Justin: Being totally honest, the

first that popped into my head was Danger

Club #1, which I've already discussed. I think it was just so efficient in

hitting most of my criteria, slick art, a great hook about teen sidekicks

having to step up after Earth's greatest heroes mysteriously disappear after

facing a cosmic threat, bringing something fresh to a tired set of genre tropes

in the writing department, and some terrific world-building in the form of

these retro flashbacks that flesh out the main characters. It's only on issue

#2 and I can already tell it's going to be one of my favorite series of 2012. Using

your Prophet #21 loophole, I'll go

with X-Men #30 from

Justin: Being totally honest, the

first that popped into my head was Danger

Club #1, which I've already discussed. I think it was just so efficient in

hitting most of my criteria, slick art, a great hook about teen sidekicks

having to step up after Earth's greatest heroes mysteriously disappear after

facing a cosmic threat, bringing something fresh to a tired set of genre tropes

in the writing department, and some terrific world-building in the form of

these retro flashbacks that flesh out the main characters. It's only on issue

#2 and I can already tell it's going to be one of my favorite series of 2012. Using

your Prophet #21 loophole, I'll go

with X-Men #30 from

Brian Wood and David Lopez[3].

It's one of these jumping on point issues that takes the book in a radical new

direction and functionally is a #1. The hook is Planetary meets Authority,

but with a mutant strike team lead by Storm. 4 of the 5 team members are women, which I'm

surprised isn't getting more fanfare. He sets it in a fun

corner of the world, dropping in all sorts of obscure personal like Sabra (the

mutant Mossad Agent), quirky fringe characters like Pixie and Domino, and fun

Warren Ellis inspired sci-fi/green technology/experimental propulsion stuff.

David Lopez is an artist I wasn't familiar with, but I was instantly blown away

by his John Cassaday meets JH Williams III art. It's got this really glossy and

consistent polish to it, but then a lean, kinetic, detailed, and thin line

weight that I just adore.

Keith: Justin, as I wrote that question, my 'blink' response was Animal Man #1. The faux magazine interview

in The Believer that Jeff Lemire uses

to kick off the series is, for me, the most creative and perfect introduction

to a series/character that I've read in the last twelve months. Buddy Baker and

the whole Animal Man 'famn damily'

were entirely new to me as was Lemire and artist Travel Foreman. This was a

case where my only disappointment about the first issue was only that I was

going to have to wait thirty days to read the next issue. Animal Man is also a good example of how quickly a series can lose

its momentum when an artist leaves or the narrative gets bogged down in

cross-overs and drawn-out story arcs. If I were to go (a lot) less mainstream,

I would suggest Matt Kindt's Mind MGMT

from Dark Horse. I'll grant that this comic isn't for everyone given its genre

(conspiracy theories and clandestine WTF?! organizations) and that its simple,

spare art (Kindt writes and draws each issue) isn't in the same league with

most cape comics. Mind MGMT is a

story that can only be compared to SEAL training when someone is left broken

and busted out in the middle-of-nowhere with only a half-chewed dull eraserless

pencil and their wits; unpredictable and a hell of a lot of fun as long as you're

willing to ride the ride.

Keith: Justin, as I wrote that question, my 'blink' response was Animal Man #1. The faux magazine interview

in The Believer that Jeff Lemire uses

to kick off the series is, for me, the most creative and perfect introduction

to a series/character that I've read in the last twelve months. Buddy Baker and

the whole Animal Man 'famn damily'

were entirely new to me as was Lemire and artist Travel Foreman. This was a

case where my only disappointment about the first issue was only that I was

going to have to wait thirty days to read the next issue. Animal Man is also a good example of how quickly a series can lose

its momentum when an artist leaves or the narrative gets bogged down in

cross-overs and drawn-out story arcs. If I were to go (a lot) less mainstream,

I would suggest Matt Kindt's Mind MGMT

from Dark Horse. I'll grant that this comic isn't for everyone given its genre

(conspiracy theories and clandestine WTF?! organizations) and that its simple,

spare art (Kindt writes and draws each issue) isn't in the same league with

most cape comics. Mind MGMT is a

story that can only be compared to SEAL training when someone is left broken

and busted out in the middle-of-nowhere with only a half-chewed dull eraserless

pencil and their wits; unpredictable and a hell of a lot of fun as long as you're

willing to ride the ride.

Mr. Giampaoli (dude writes like a fiend) can be found at http://thirteenminutes.blogspot.com/ and follow him on Twitter @thirteenminutes for some of the best (and boldest) comic book criticism anywhere.

[1]

Justin took me to task on my ‘Gandalf analogy’ at

this point in the discussion. I edited it out of our discussion, but you can

read the whole damn thing here: I'm [Justin] struggling to come up with a Gandalf retort,

but uhhh... well, I guess a lot of people complain that when we first meet

Gandalf, the scenes in the Shire take forever and a day to conclude, but that

should NOT be attacked for decompression using my criteria because it's germane

to the story. I think Tolkien lingered there, at least in part, to show what an

idyllic and innocent place ye olde Hobbits were from to juxtapose that with

their involvement in the impending war. Contrast that to, I don't know, if

they'd shown Aragorn and the fellas camping out at Weathertop in real-time for

hours on end and I don't think you're adding much to the narrative, just boring

the audience with irrelevant decompression.

[3]

Álvaro López is also listed as an artist on X-Men #30. The colors are done by Rachelle

Rosenberg.